ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN THE WATERTOWN DAILY TIMES, MAY 21, 2024

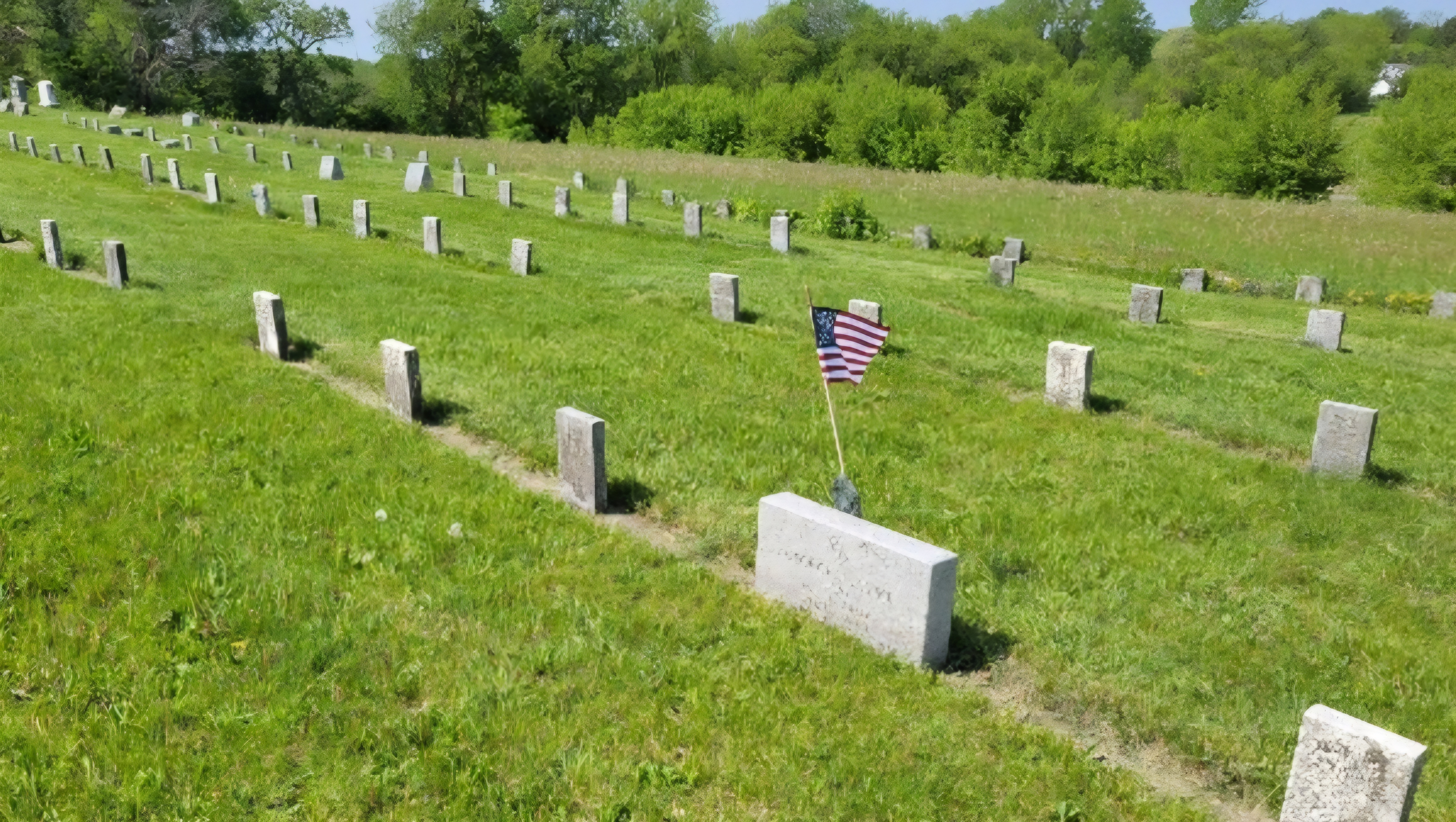

At the northeast edge of Watertown, Wisconsin lies the Evangelical Lutheran Cemetery. Early in the 20th Century, a distinct part of the grounds was set aside for the people who lived at Bethesda Lutheran Home. From its founding in 1904 until 2018, Bethesda (now known as AbleLight) operated in Watertown and was home to hundreds of men and women with developmental disabilities.

Each year on Memorial Day, a strange sight appears in the midst of this section of the cemetery set aside for institutionalized people. A lone flag is planted by the stone bearing the name of George F. Henke.

Disability and War

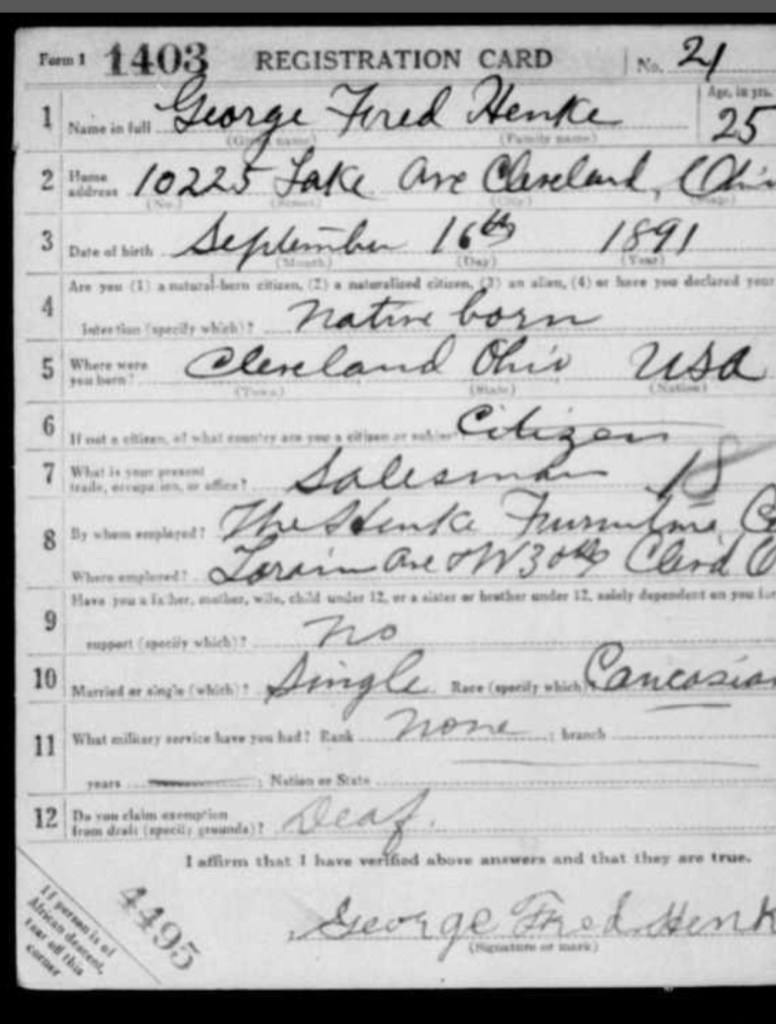

We know a few things about Mr. Henke. He was born in Ohio in 1891 and worked in his father’s furniture store. His draft registration card tells us he was single and had no dependents. It also tells us he was deaf.

Eventually, he enlisted in the army and served his country for six months until his discharge. His original disability, together with his experiences in the Great War, eventually led to his residing at Bethesda in Watertown. He remained there until his death in 1958. There are many things we do not know about George Henke, but his life opens an important chapter in our nation’s military history.

The connection between war and disability is most often seen as a cause-and-effect relationship. People go to war, and they come home changed. For many, those physical and psychological effects are disabilities that will last a lifetime. In the conflicts of the past century, hundreds of thousands of veterans have returned home as people with disabilities. But there is another layer to the story—those whose disability came first.

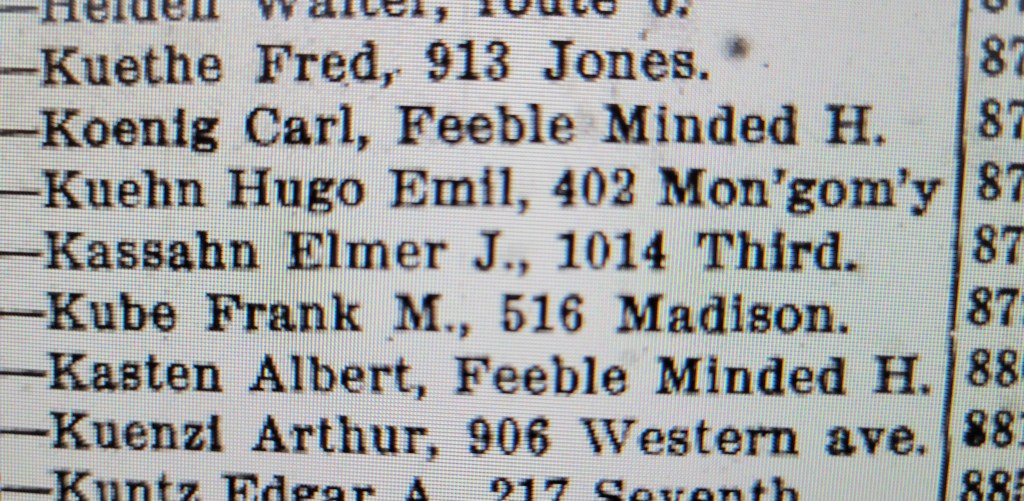

The July 19, 1917 edition of the Watertown Daily Times lists the names and addresses of those Watertown residents who registered for the draft immediately following the Selective Service Act. Among those listed were 18 men whose address simply reads “Feeble Minded H.” Before it was called Bethesda, the institution was known as “The Evangelical Lutheran Home for the Epileptic and Feebleminded”. The Feebleminded Home.

In many circumstances, disability is a legitimate exemption from military service. However, the inclusion of people with what we now know as intellectual and developmental disabilities has been far more common and far more recent than most people realize.

Project 100,000

At the height of the Vietnam War, there was a critical need for military personnel. In October of 1966, Defense Secretary Robert McNamara launched his Project 100,000 initiative. In effect, the project adjusted the minimum intellectual requirement to a level meeting today’s understanding of intellectual or developmental disability. Through either the draft or enlistment, more than 350,000 men were brought into military service through the Project. Most went to Vietnam, and about half of those were assigned to combat units.

Today, Project 100,000 is generally acknowledged as a failed experiment that did far more harm than good. Those soldiers who did return had further psychological wounds to bear. Over time, they were less likely to receive necessary education, and had statistically lower incomes than their non-veteran counterparts with the same intellectual capacity. The project ended in December 1971.

According to Hamilton Gregory, author of the book McNamara’s Folly: The Use of Low-IQ Troops in the Vietnam War1, regular service personnel were well aware of this new group. The Project inductees quickly became labeled as “misfits”, “McNamara’s Folly”, or even “McNamara’s Morons”. Illiteracy was common among the Project’s inductees, and many had an IQ of below 75. Gregory, who was assigned to lead some of these soldiers, reported that some did not even know the US was at war until they arrived in Vietnam. Still, their service and sacrifice were remarkable. They were far more likely to serve in combat, had more than three times the casualty rate of other Americans serving in Vietnam, and the rate of friendly fire was five times that of the rest of the Army.

They served

Today, people with developmental disabilities are among those whose dignity is repeatedly forgotten and for whom simple respect often remains elusive. Perhaps this is a time for us to remember that they once stepped forward—some at the cost of their own lives. They were called to a purpose beyond themselves, took responsibility, and did what their country asked of them.

The names of Project 100,000 soldiers killed in the war are not found in segregated cemeteries. Rather, they are etched alongside their military comrades on the Wall in Washington, D.C. That place of honor and remembrance is precisely where those names belong.

_____________________________

- Gregory, H. (2015) McNamara’s Folly: The Use of Low-IQ Troops in the Vietnam War. Infinity Publishing. ↩︎